Winner of Writer’s Type Best First Chapter Contest (2013).

Women in the sultan’s capital, no matter their rank, tended to die uneventfully: strangled in the dead of night, sewed neatly into weighted flour sacks, tipped into the Bosphorus along with the rest of the week’s refuse.

A calligrapher, imprisoned for reassembling the word of God, might have expected the same treatment. She had drawn human and animal forms from holy words and invocations, compact chronograms with diacritical marks for eyes and letters for limbs, but the holy men didn’t care to see the Bismillah reflected in their own faces. Their God belonged on the page, as immobile and resolute as a citadel. They sentenced the calligrapher to death.

Her jailers talked of the Executioner’s Race. She begged them to pass a message to the Bostanci-Bashi, the Chief Gardener, who doubled as the sultan’s executioner.

“Let me race,” she said. “Let me die an honorable death. After all, as a woman I have no chance of winning, and think of the spectacle you would have on your hands as I flounder through the bushes, thorns, and weeds.”

Her jailers shook their heads and said the race was the privilege of condemned notables—a deposed vizier, perhaps, or a chief eunuch—not for someone as ordinary as her.

The calligrapher scratched a petition on the walls of her cell with the husk of her reed pen. She called in the jailers and they, unlettered and afraid, ran to the Bostanci-Bashi. The Chief Gardener examined her markings by candlelight and clucked his tongue.

“Is this the way you honor your master’s profession?” he asked. “By daubing God’s script on prison walls?”

“I’m sure you are right, sir,” the calligrapher said. “Women are always impatient. I simply couldn’t wait for the right conditions.”

“The right conditions?”

“As a gardener, you wouldn’t plant and sow unless the soil was favorable?

“Of course not.”

“And you wouldn’t use an inferior spade and hoe?”

“No.”

“And as an executioner, you wouldn’t slice off my head with anything but the sharpest blade.”

“Woman, what are you saying?”

“That you, sir, possess infinite patience and expertise. A lesson I would do well to learn.”

An hour later, a sheet of paper and a tortoise shell full of ink arrived at her cell.

The calligrapher licked and spat on her right hand until her mouth drained dry. She removed the grime and dead skin of the dungeon the best she could with the hem of her pelisse. She looked down at the materials sent by the Bostanci-Bashi and sighed. The ink was thinly mixed and flakes of soot floated to the surface like crumbs of bread in a bowl of soup. The paper was coarse and unburnished, lacking the shiny finish of the quince kernels and egg white she was accustomed to working with. The pen was unkempt; she longed for a penknife to trim its rough edges, to hone it in preparation for the words forming in her head. She sat cross-legged and balanced the paper on thigh and knee. She felt it tremble a little and waited for it to settle. She began to write.

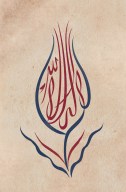

When the Bostanci-Bashi looked at the bold strokes and curving letters climbing the page, he had to blink twice before he saw that the calligrapher had woven her petition into the shape of a flower, of a type that his predecessors had once grown in the palace gardens. In his dreams he had felt the texture of this flower on his fingers, breathed its slight scent. He arranged for the petition to be framed. Eventually he sent word that the calligrapher would race against a bostanci, a junior gardener. They would begin on the top terrace of the palace’s outer garden and run down to the fish-house gate in the sea wall. If the calligrapher reached the gate first, her life would be spared.

#

The calligrapher stood at the apex of the palace gardens and looked down at the sea. Half-starved, eyes burning in the sun’s glare, she could barely stand. Her green pelisse was torn, her shoes and veil had long since disappeared, and her hair, hacked off by the jailers, grew like black gorse across her skull. Only her hands remained defiant. Her fingernails were dark, henna-stained tips. On her left palm she had painted the letters of her name; on the right, the words Insha’Allah—God willing. The junior gardener stood at her side, broad-shouldered, his bare arms a document of cuts and scratches from the flora in his care.

At midday, a cannon boomed and the two figures began their descent to the shoreline. The young gardener was racing for pride; it had been many years since his brethren had lost the race against a condemned man, let alone a woman. The runners passed through and around thorny rose bushes, woods of guarded cypress, and, massed like vast armies reposed after battle, beds of hyacinths, narcissi, and tulips. Bostancis stood guard at each tier. Men dressed in similar sleeveless tunics and blue breeches were differentiated by the color of their belts: red for the Corps of Vine Grafters, yellow for the Corps of the Haystore, and blue and green for the rival Corps of Okra and Cabbage.

If the calligrapher veered from the path onto the sultan’s flower beds, she would be struck down by the axe of the nearest bostanci before the race had run its course. She weaved around the aprons of attentive tulips, moving sideways and sometimes backwards to find a path, constantly thwarted as she tried to break into a steady run.

The junior gardener had already passed between the ranks of the Grand Turk’s tulips—the Delicate Coquettes and Pomegranate Lances with their taut stems and silken petals. He knew the narrow paths well; he had worked this soil since he was a boy. His mind began to wander. Tomorrow he would be permitted to collect, cut, and place five of the finest specimens in filigree glasses in the sultan’s private kiosk on the top tier of the gardens overlooking the Golden Horn. The sultan himself would choose one of these flowers to be placed in his private chamber. It would be a great honor for the young bostanci, a mark of the respect he could now expect from his colleagues.

But something was happening behind him. The calligrapher had arrived at a bed of the sultan’s most prized tulips, the reddish/orange Mahbub, or Beloved, a single bulb of which a collector once offered one thousand gold coins to possess. The sultan himself had named this particular cultivar; its petals reminded him of the curve of the new moon that crested his beloved city on spring evenings. The calligrapher stopped dead in her tracks and stared. To the observing bostancis, it seemed she had given up on the race and decided to spend the remaining moments of her life enjoying the tulips’ beauty. The calligrapher took a few steps back as if to gain a better perspective. The young gardeners nodded to each other. The woman was misguided and perhaps crazy, but she could appreciate beauty and was courageous; she would die a noble death. Then, without warning, she dashed toward the tulip bed, pelisse billowing around her, hennaed fingers glinting in the sun.

The bostancis drew their axes; it seemed, after all, that the woman was a reprobate and would care no more about crushing the sacred flowers than stepping on a beetle. As they advanced toward her, the calligrapher began to dance, spin, and skip between each row of tulips. There was certainly no path cut through the meticulous flower bed; even a rabbit could not have forged its way between the tight ranks, but she pointed her bony toes downward and landed on the tiny strips of earth that separated each line of flowers. The bostancis raised their axes and waited for the calligrapher to crush even a single petal. The Mahbub swayed and dipped their heads as if caught by a sudden breeze. In a few seconds, the calligrapher had traversed the flower bed without damaging a single bloom.

When the calligrapher passed in a flurry of silk and skin, the bostanci felt the earth exhale. Standing in her wake, he understood, for the first time, the true nature of the soil.

The bostanci’s colleagues, not believing the evidence of their own eyes, surrounded the calligrapher. They prodded her with their rakes and hoes as if she were a snap-jawed plant. They might have returned her to the earth had not the Bostanci-Bashi arrived on the scene. He hadn’t seen the calligrapher dance over his precious tulip beds; he had been waiting for her at the Fish-House Gate, garrote in hand, a woven sack crumpled at his feet like an exhausted dog. The reaction of his men told him that he would not have the pleasure of tightening the knot around the woman’s neck and consigning her memory to the Golden Horn. But he restrained his young charges in case the calligrapher had some strange, magical attribute to use against him.

#

A week later, after the calligrapher’s sentence was commuted to a seven-year exile, an envelope arrived at the Bostanci-Bashi’s quarters. It contained one sheet of thick, creamy paper, emitting the faintest aroma of quince. He recognized the loops and curls of the script immediately, the elasticity of letters that could not be contained. Above a short note that read simply, ‘from the beneficiary of your expertise,’ the Bostanci-Bashi beheld a stork in full flight, its plumage a network of loops, lines, and dots, a fragile fluted neck curving into a tipped beak.